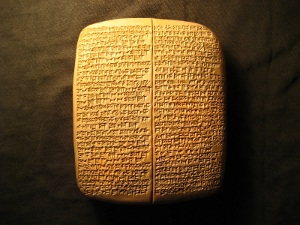

Julia Assante received her doctorate in Archaeology and Art History of the Ancient Near East from Columbia University. On invitation, she studied the cuneiform languages of Sumerian (the first known written language) and Akkadian (the first known Semitic language) at Yale. She taught at Columbia, Bryn Mawr and the University of Münster and excavated in Crete (Minoan levels) and Israel. She has given talks at major universities and conferences in the United States and Europe and has written numerous scholarly articles.

Her specific area of interest is religion, magic and sexuality, three categories that were closely interconnected in antiquity. Many of her publications revise previous scholarship on the ancient Near East, especially where it concerns Innana/Ishtar and her cult. Innana in Sumerian or Ishtar in Akkadian was the goddess of sex, war and fate. She was also Mesopotamia’s longest lived and most popular deity. Under her special protection were women called harimtu’s, who previous scholars believed were prostitutes. Julia has since shown that harimtu’s were in actuality a social class for women who had no patriarchal status, meaning they did not live under the legal protection of a father, brother or husband. She has also shown that there is no evidence for fertility cults or rites in Mesopotamia, as was previously believed, nor is there any evidence for sacred prostitution, male or female. Such concepts are grounded in seriously flawed nineteenth-century thinking, not in antiquity. Her work continues to influence other fields, such as biblical studies and Greco-Roman history. She has been named in Der Spiegel (Germany’s equivalent to Time magazine) as the leader of a movement challenging the status quo of gender scholarship in antiquity.

One of Julia’s greatest passions is how scripture and Christianity itself formed within the wider, older socio-political context of the ancient Near East. For academics like her who write ancient history from a perspective of a thousand or more years before the writing of scripture, the Bible is nearly a modern work. Although the afterlife plays an enormous role in the formation and maintenance of any religion, it was largely the denial of an afterlife that made ancient Judaism unique. By the time of Jesus’ birth, denial had spawned a myriad of Judaistic sects, such as the Essenes. These sects, which were outside official Judaism, were generally apocalyptic. For them an afterlife was only possible after the apocalypse and it was to be situated on earth. In Chapter Seven of The Last Frontier, Julia traces the conceptions of the afterlife as they developed in the world’s oldest religions and how these conceptions kept changing in order to meet shifting socio-political aims.

You can find a list of her academic publications on Academia.edu by clicking here.