Angola’s Prison Hospice Documents Innmates’ Deathbed Visions

Marilyn Mendoza, author of We Do Not Die Alone, a book about deathbed visions, has graciously sent me her extraordinarily interesting article on nearing-death phenomena in Angola, the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Not all the deathbed visions are pleasant.

Angola, also known as the Alcatraz of the South or the Farm, is the largest maximum security prison in the US. More than 85% of the 5,100 inmates are expected to die there. Formerly, prisoners died alone and were buried in cheap boxes in numbered graves in the penitentiary’s cemetery. But in 1998, Angola pioneered a nationally acclaimed hospice program in which inmates are the caregivers of the prison’s dying. Marilyn said that interviewing the inmate hospice workers was definitely one of the most interesting experiences of her life. Because of it, she has come to the conclusion that the way to rehabilitate people is by helping them develop compassion. During the interviews with the hospice prison workers, she remarks, “It was very touching to see the tears in these men’s eyes as they spoke about the dying.”

In fact, Marilyn turns out to be right. The effort the hospice volunteers make to create a reverent ambiance around the dying has affected the entire prison population. The program has transformed a one of the most violent penitentiaries into the least violent maximum-security prison in the US. Just as uplifting, however, is the frequency with which criminal “lifers” experience the promise of ineffable love, beauty, and forgiveness to come as they draw their last breath.

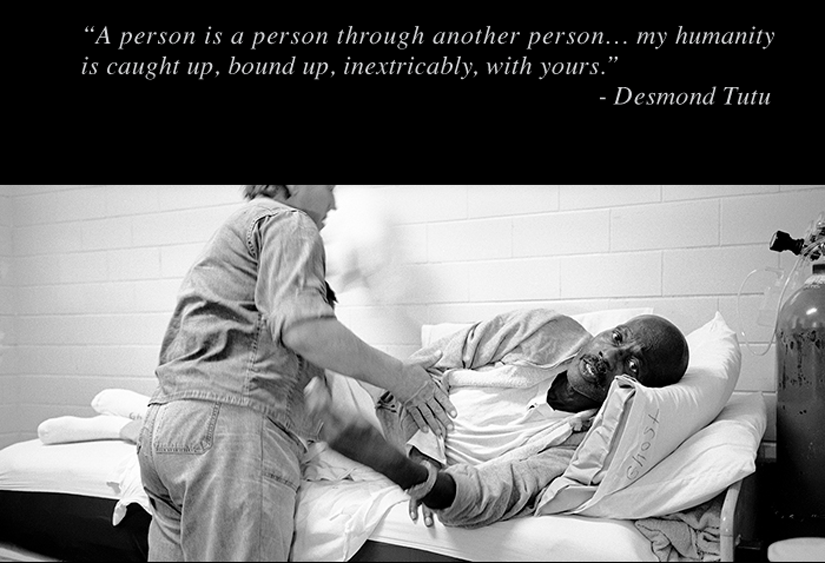

This picture, entitled “Grace Before Dying,” is part of an award-winning photographic documentary by Lori Waselchuk that chronicles Angolas prisoner-run hospice program. Through a Distribution Grant from the Open Society Documentary Photography Project, Waselchuk collaborated with the Angola Hospice Volunteer Quilters to build a traveling exhibit featuring photographs from her project and quilts commissioned for the exhibit. For more information, click here.

DEATHBED VISIONS of PRISONERS

by Marilyn Mendoza

(Originally printed in “Vital Signs,” Fall 2011, Volume 30, Number 3)

While researching my book “We Do Not Die Alone: Jesus is Coming to Get Me in a White Pickup Truck”, I discovered that not all deathbed visions (DBVs) are comforting and pleasant. (A DBV is a vision or experience that the individual has before dying. It may occur immediately before death or days or even weeks prior. A typical vision is that of a deceased family member coming to take the dying away.) Since then, I have been intrigued by distressing DBVs (DDBVs) and who might experience them. In fact, when I was doing my initial literature review on DBVs for my book, I did not even know that distressing experiences existed as these events were rarely mentioned. If referenced, it was usually one line in small print at the bottom of the page. All the sources suggested that these deathbed visions were comforting and pleasant experiences but some of the accounts in my research suggested anything but that. For example:

“My first hospice patient to die was just a few years older than me. We had spoken on admission about getting things in order. The doctors had told me she only had a few days to live. She was in denial, although her platelets dropped dramatically with each infusion. A week later, on a Sunday morning, I was called by her son. On arrival, it was evident that she was actively dying. She was still talking at times. When she would moan, I gave her pain meds. After a couple of hours, she had definitely declined. Her five children, mother and sister were at her bedside. She sat straight up in the bed and said, “Where is the fire? I smell smoke!” and she collapsed back on the bed. A few minutes later, she sat up in the bed and said, “Get those things off my legs” and was rubbing her legs. The last thing she said to me was, “I waited too long,” and then she died.

The existing research into distressing experiences has been documented with Near Death Experiences (NDEs).In 1975, when Raymond Moody published his book “Life after Life” all the events reported were of a positive and comforting nature. However, it is through the work of Nancy Evans Bush and others that these distressing experiences have been brought to the forefront making them an accepted part of the NDE phenomena. Three types of distressing experiences have been identified. The first is a typical NDE that is perceived as frightening. The second is finding oneself in a “void” of nothingness and the third being in Hellish surroundings.

We may not know why one person has a positive experience and another a distressing one. We do know, however, that independent of the type of experience the after effects tend to be similar. Most peoples’ lives tend to be changed for the better. They lose their fear of death; they become more loving and accepting and have a changed view of life. But what happens to someone who has a distressing DBV? We do not know. They die and do not come back to tell us. The literature on NDEs suggests that we are all capable of having distressing experiences but is that true for DBVs? What better population to explore the question of who is likely to have distressing DBVs than a population of murderers and rapists?

Angola is a maximum security prison that has been called the bloodiest prison in America. It houses 5000+ men whose crimes range from murder, rape, armed robbery to drug offenses. The majority of men who come to Angola die there. Prisoners, like many of us, not only have a fear of dying alone but have an even greater fear of dying in prison. Angola is one of 17 prisons in the United States that has a hospice program. The Angola Hospice program has been the subject of an excellent documentary produced by Oprah Winfrey entitled “Serving Life.” Prior to Warden Burl Cain bringing hospice to Angola in 1998, Angola had a most checkered history of its treatment of the dying. Hospice has been a welcome addition not only for the inmates but for staff as well. The dying inmates are cared for by hospice inmate volunteers: murderers taking care of the dying at the end of life. There are many aspects to my research there. Exploring the types of death bed experiences these men had was one of them.

In the general free population, statistics reflect the vast majority of the dying experience peaceful and comforting DBVs (98%). It is estimated that approximately 2% have distressing experiences. Exact numbers, however, are unknown. Many people do not want to share information about pleasant or distressing experiences as they fear their loved one would be thought of as a “bad” person.

Twenty nine inmate volunteers were interviewed with a range of experiences with the dying from 5 months to 13 years. Inmates who are selected to be volunteers in Angola’s hospice go through a rigorous screening and training process before they begin working with the dying. These volunteers become involved in all aspects of patient care. They bathe them, change diapers, sit with them and hold their hands as they die. Volunteers work in shifts so that someone is always with the dying. They say that they become like family and in some cases are their only family as many are abandoned by their outside families.

Volunteers were asked, “Of the dying you have been with, have any of them talked about unusual experiences or seeing people, places or things that you could not see?” Twenty six of the 29 volunteers said “yes.” According to the caretakers, not everyone had a DBV that they were aware of but the vast majority of the men did. The predominant belief among the volunteers was that these were spiritual experiences and felt them to be spiritually moving. A lesser number believed they were hallucinations and felt indifferent toward them.

As is common with most people, the majority of the DBVs the caretakers described were pleasant. Family members were the most frequently seen vision. Caretakers reported that the dying saw mothers, grandmothers, sons, fathers and other family members. The dying spoke of people waiting for them and calling them to come home. They told the caretakers about waiting for a bus and walking through a gate. One even spoke of seeing family coming to get him in a Cadillac. The dying also spoke of angels, beautiful gardens, gates and the Light. The men stared in corners of the room, at the wall and the ceiling. They reached for and called out to the deceased they saw. In other words, the dying prisoners saw and experienced the same things as the general population.

The inmate volunteers did talk about some patients who were bitter and angry until they took their last breath. They were angry at everyone and everything but especially at death. Only one account was given of a distressing experience for a patient. According to his volunteer, the patient spoke of seeing dark beings moving from the wall to the floor coming to get him. He was said to have been so frightened that he tried to get away by crawling out of the room. The volunteers stated that as some approached death, they were “restless, fighting, fussing, and arguing” with someone unseen. One man thought he could avoid death by never lying down. He died on his knees by his bed.

While there are three basic types of DNDEs, given the limited sample size, specific types of DDBVs can not be identified. Clearly additional exploration is needed in this area with larger numbers. It does seem as though the image of a frightening form moving up the body of the dying, as a specific type of experience, deserves further exploration. This image was also noted in the accounts in my book. What happens after their death remains a mystery as well as the reason that one might have this type of anomalous experience.

Marilyn A. Mendoza, PhD

(Reprinted with permission from The International Association for Near Death Studies, www.iands.org)